Appointing Australia’s High Court judges is too potent and pervasive an act to be solely a perk of the government of the day, says Prof George Williams. He calls for a non-partisan, non-ongoing commission to take over the crucial role of recommending a shortlist, with the government having the final choice.

Appointing Australia’s High Court judges is too potent and pervasive an act to be solely a perk of the government of the day, says Prof George Williams. He calls for a non-partisan, non-ongoing commission to take over the crucial role of recommending a shortlist, with the government having the final choice.

By Prof George Williams,

CLA member Appointments to Australia’s High Court always involve power and politics. The Rudd Government’s replacement of Chief Justice Murray Gleeson, due by the end of August 2008, will be no different. Every government wants to appoint one of Australia’s best lawyers. However, they also look for someone who might decide disputes in a way that matches the Commonwealth’s policies and its preferred approach to the law and the Constitution. A good example is a tendency found in most judges chosen by Labor and Coalition governments. Both have looked to people they think will favour a broad reading of Commonwealth power over that of the states. The fact that only the Commonwealth has the power to appoint High Court judges has undoubtedly had a major impact. Few lawyers with a strong belief in states’ rights have been asked join the court. The result has been the ascendancy of the Commonwealth over the states in most battles over the division of power. The political nature of High Court appointments was a deliberate feature of our 1901 Constitution. It was included as part of an elaborate system of checks and balances. Just as the High Court interprets and enforces the constitutional limits of the Federal Parliament and government, so too can those institutions check the court. While governments appoint the judges of the court, Parliament can dismiss them on the ground of ”proved misbehaviour or incapacity”. The Constitution actually says very little about who should sit on Australia’s highest court. Section 72 merely states that the judges ”shall be appointed by the Governor-General in Council”. In practice, this means that the Governor-General makes the appointment on the advice of the government, that is, the Prime Minister and his or her Cabinet. Other than prohibiting the appointment of judges who have reached the age of 70, the Constitution makes no mention of qualifications or background, and contains no other procedural requirements. It does not even require that the appointee be a lawyer. Parliament has set out a little more detail in the High Court of Australia Act. It requires that an appointee be a judge of a federal or state court, or have been enrolled as a legal practitioner in Australia for at least five years. It also says that the Federal Government must consult with State attorneys-general, with no mention being made of the Territories. This consultation usually takes place through an exchange of letters, but is tokenistic and never seems to affect who is appointed. It has certainly not worked for South Australia or Tasmania, which in over a century have yet to have even one High Court judge appointed. The law fails to set out any criteria for selecting a High Court judge. Attorneys-general instead routinely say that judges are chosen on ”merit”, a term vague enough to justify almost any choice. Merit has meant more than which person has the best legal skills. Governments over many years have picked High Court judges out of a large pool of talented candidates with the final choice sometimes influenced by partisan politics, the state in which a person lives and personal friendships. It has long been argued that we should reform how High Court judges are appointed. It is not hard to see why. The lack of any transparency or meaningful criteria leaves the appointment within the gift of the government of the day. This benefits whoever is in office and is not something that either side of politics has sought to change. Many other nations have reformed their process of judicial selection. Australia now lags behind a long list of countries that have sought to reduce the opportunity for political patronage and to increase public confidence in the courts. Australia has three main options for change. • The first is to elect judges, just as we elect our politicians. Popular elections are held in 21 states in the United States, but not in any other democratic nation. The idea has some popular appeal given that judges make decisions about the law for the whole community. However, choosing judges would undermine what we want from them. Judges should be independent and non-partisan. They must do justice according to the law and not according to who has voted them in. • In the second option, governments could nominate someone, with confirmation by a vote of parliament. Confirmation hearings are held for appointments to the US federal courts. This process would allow heightened public scrutiny and could place a popular check on government. However, it could still lead to political appointments, as the USA has shown with heated confirmation battles over appointments to the US Supreme Court. Given Australia’s rigid party system, it could also increase partisanship in judicial selection. • The third, and best, option is to create a judicial appointments commission to advise the government. Commissions have been adopted or are being considered in Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, Israel, Britain and parts of the USA. They have proved more fair and open and have produced judges of the highest quality with more diversity in gender and background. An Australian judicial appointments body should consist of lawyers and non-lawyers. Some lawyers argue against lay people serving on such a body. However, lawyers should not have a monopoly on advising on who becomes a judge. Judges should be chosen in a way that reflects that they serve not the legal profession but the community at large. The judicial appointments commission should be activated for each High Court appointment. It should consult widely and consider interviewing candidates in preparing a short list of names for the government. Those on the short list should be chosen against clear and publicly accessible criteria relating to their legal skills and professional and personal qualities. In almost all cases, the government would be expected to select a person from the short list. It should be able to appoint someone else only if it discloses the reason in a public statement. The final decision would still be one for the government. Attorney-General Robert McClelland has got off to a good start in making changes to the selection of Federal Court, Federal Magistrates Court and Family Court judges. He has placed public advertisements seeking expressions of interest and nominations and has consulted more broadly with people and professional bodies. The A-G has also established an advisory panel of former High Court Chief Justice Sir Gerard Brennan, Federal Court Chief Justice Michael Black, NSW acting Supreme Court Justice Jane Mathews and a senior officer of the A-G’s Department. Unfortunately, these innovations have not been applied to the High Court. It is hard to understand why not, except that when it comes to Australia’s top court the government wants to maintain its unfettered say. A further problem is that the A-G’s panel includes only lawyers. The community should get a look-in, as should academics. In my experience, members of the community often raise issues that lawyers too readily forget.

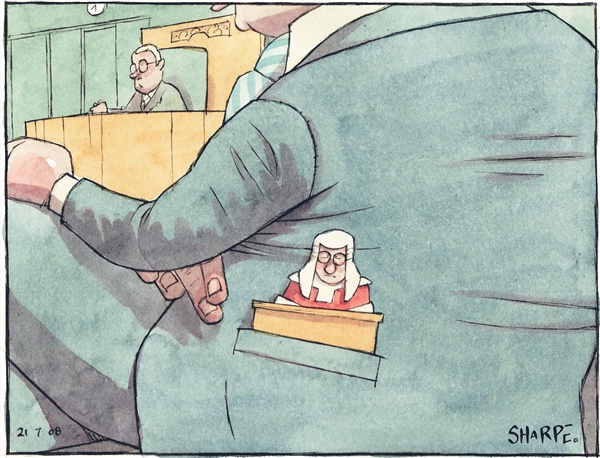

George Williams is the Anthony Mason Professor at the University of NSW, a visiting fellow at the ANU College of Law, and a member of Civil Liberties Australia. Ian Sharpe illustrates and cartoons for the Canberra Times. Both the article and the illustration first appeared in that paper on 21 July 2008.

Caption: Cartoonist/illustrator Ian Sharpe’s take on the Prof Williams article.