Reason deserts justice when jurors anonymously cobble together shaky evidence while locked away like criminals. Crispin Hull reviews how one notorious case went astray when the wholly improbable met the then-impossible.

Forensic guilt can be very ropey

By Crispin Hull

Extended excerpt from an article on the final stage of the Lindy Chamberlain tragidrama.

I covered the Chamberlains’ appeals – the ‘Dingo Took My Baby’ case – in the Federal and High Courts in 1983 and 1984. That and subsequent events have been an instructive experience.

At the end of the Federal Court appeal I was convinced of Lindy Chamberlain’s guilt. Ian Barker QC, for the Crown, put an incisive case, as he did at the trial.

In the Federal Court Barker was there to argue that the jury’s guilty verdict was safe and satisfactory. He used the rope analogy. Each strand of evidence, he said, was not in itself convincing, just suggestive of guilt. But taken together they formed a strong rope.

He cited the foetal blood in the Chamberlain’s car; the infrared image of a hand on the jump suit (which had been found a week later); blood splatter evidence; vegetation; sand grains only on the surface of the blood drops; evidence of dingo jaw width; scissor-like slicing of the fabric of the jump suit and so on.

It was like an early version of CI. Very convincing when taken together.

It convinced the Darwin jury, especially when another ingredient was added.

Barker told the jury that Territorians knew that crocodiles were dangerous and could take a baby or an adult, but that dingoes just did not do that. Territorians knew that.

It was the frontier mentality. Lindy’s lawyer was from Melbourne – down south where they don’t understand these things. And the jury bought it.

They bought it despite the judge, Justice James Muirhead, summing up in a way that a sophisticated jury would suggest an acquittal was warranted. I have it on unreliable hearsay evidence (but I can get no better) that Muirhead was aghast at the guilty verdict and rang a judicial colleague to say so.

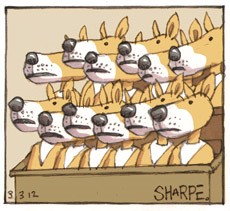

The jury: random, anonymous…and no reasons given

The Chamberlain case is yet another example of the defects of the jury system. Juries do not have to give reasons for their decisions. They are required to act in haste – they are virtually locked in a room until they come to a verdict. They act anonymously. They are selected at random with no testing of their capacity to make decisions.

Worse, once they decide, the appellate system gives far too much weight and respect to their verdict. Appeal judges are not allowed in law to substitute their own conclusions for the jury’s. They can only overturn a jury verdict if it is shown to be unsafe, unsatisfactory or dangerous.

It is a damn silly process because juries give no reasons. We can never know whether in this case or any other a jury gave weight to irrelevant matters: “We know as Territorians that dingoes do not take babies or attack humans.” “She belongs to that weird religion.”

That said, it is hard to blame the jury in the Chamberlain case for getting it wrong because of the way the case was put to them. They were invited to conclude that when you exclude the impossible (that the seven or eight pieces of scientific evidence were wrong) you have to conclude the improbable (that a mother without any motive killed her child and somehow disposed of the body).

In the words of Chief Justice Harry Gibbs and Justice Anthony Mason in the High Court, “The jury should decide whether they accept the evidence of a particular fact, not by considering the evidence directly relating to that fact in isolation, but in the light of the whole evidence, and that they can draw an inference of guilt from a combination of facts, none of which viewed alone would support that inference.”

Shaky bits comprise circular trap

That reasoning invites the acceptance of individually shaky bits of evidence because overall they point to a conclusion of guilt. Worse, a jury bombarded with scientific evidence could fall for the trap of circular logic by allowing a hunch or gut feeling of guilt to emerge and then reassuring themselves that the scientific evidence supports it.

It is the Barker rope trick. It is still good law.

It might be fine when the evidence is a combination of ordinary circumstantial evidence, but not if it is scientific evidence. Science is science, not conjecture. The science should be convincing or should be excluded from the jury.

People chosen at random are not likely to be equipped to cope with contentious scientific evidence.

In the Chamberlain case, the reverence that six of the eight appeal judges (three in the Federal Court and three of the five in the High Court) had for the jury verdict – respect for the good sense of common person’s view of the world – led them astray.

The jury did not apply good sense – why would a mother on holiday kill her baby and, having done so, concocted a story about a dingo taking her baby? The judges should have applied good sense, but couldn’t because of the state of the law and because they had no idea how the jury came to its verdict.

We now know the science was dud and we know a lot more about dingoes…

ENDS

Crispin Hull, journalist and lawyer, is author of books on the High Court and on Canberra. A former editor of the Canberra Times, he has taught journalism at U. Canberra for many years. He is chair of the national board of Barnardos and an advisor to an Australian Bureau of Statistics governance panel. His blog is at http://www.crispinhull.com.au

This article first appeared in The Canberra Times on 3 March 2012, as did the illustration by Ian Sharpe (who is a Civil Liberties Australia member).

Barker said my book, Trial by Voodoo: How the Law Defeats Justice and Democracy (Random House 1994, now at netk.net.au/whittonhome.asp) was “the silliest book of the decade”.

I replied that he might very well be right, but he was the wrong person to say it: he was the guy who got the dingo off…