Rarely can we enjoy an historian writing about the history he himself created. But Ken Buckley – founder and for 40-plus years the fulcrum of the NSW Council for Civil Liberties – was determined to complete his autobiography before succumbing in 2006. His partner in life and liberties, Berenice Buckley, has published the story which is at once about the life of one man, and the liberty (or otherwise) of a state and its people. CLA President Dr Kristine Klugman, who was there at the beginning, reviews the book.

Rarely can we enjoy an historian writing about the history he himself created. But Ken Buckley – founder and for 40-plus years the fulcrum of the NSW Council for Civil Liberties – was determined to complete his autobiography before succumbing in 2006. His partner in life and liberties, Berenice Buckley, has published the story which is at once about the life of one man, and the liberty (or otherwise) of a state and its people. CLA President Dr Kristine Klugman, who was there at the beginning, reviews the book.

Book review

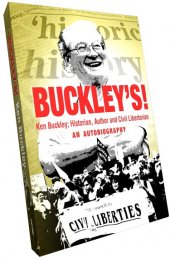

Buckley’s: Ken Buckley; Historian, Author and Civil Libertarian – An Autobiography

People who enjoy lively commentary on the social, political and economic environment of our society in its recent history will be interested in reading this book. If you are concerned for civil liberties and human rights, you will be drawn into this fascinating account of the influence of one person in creating an organisation to defend rights in our society.

The autobiography is notable as much for Ken Buckley’s observations on society as for its personal story. Through Buck’s eyes, we see the influences which drew him to the Communist Party and socialist interpretation of history: working class father, British class system, Spanish Civil War, experiences in the Intelligence Corps in World War Two. “I have sometimes looked back in wry amusement – there was I the undisclosed communist, in clandestine operations in a body akin to the CIA” (p52). There must have been a strange and uneasy juxtaposition between Buck’s anti-authoritarian nature and army discipline.

I knew Buck for more than four decades – sounds better than over 40 years! We were especially close when we worked together on the company history of Burns Philp during the years 1981 to 1986. As I write this review, I feel very sad that he is not here to edit it!

I learned a lot from Buck: from his dedication to the task, his thoroughness and historical integrity, his sense of humour and especially his fundamental belief in a fair go, especially for the little bloke. As he freely admits, he could be a difficult bastard. Yet what I remember is his unfailing courtesy and generosity of spirit, and his grin. He held great respect for individual privacy. The introduction to this volume does not, to my mind, do him justice.

Buck’s life-long interest in Greek and Cypriot affairs is another demonstration of “…the enduring preoccupations and governing forces of my whole life; concerns with justice and corruption; with promoting the socialist objectives of equity and well-being for all; championing civil liberties and human rights” (p89). His political activism in demonstrations against Mosley’s Blackshirts and in support of unions, and later his active role against the conservatives at Sydney University were further evidence of this.

Australia’s gain came in 1952 when Buck took up a position at Sydney University, despite ASIO and MI5 attempts to keep him out. He actually resigned from the Communist Party of Australia in 1956 (as did many others), appalled by the revelations of Krushchev. He remained a socialist, though he became very disillusioned in later life with the Labor Party’s ‘economic rationalism’ and opportunism, and late in life joined the Greens.

Of his teaching of history, Buck wrote: “Curiously, nobody…raised the question of bias by conservatives in the research and teaching of history. Historians who claim to be objective and impartial are very often conservative in their views of current affairs, failing to recognise that a conservative view of the present situation colours their views of the past. In my own lectures to students, I never claimed to be unbiased, but I did present them with varying interpretations of events, so they could decide for themselves” (p147).

I can attest to the veracity of this statement: when research of BP records revealed the unsavory episode of ‘blackbirding’, Buck wrote it up in a factual manner, putting it in the political and moral context of the day. This was accepted by the Managing Director, David Burns.

Buckley’s life-long work was teaching and his history writing, which was prolific and varied.

With me as co-author, The History of Burns Philp: an Australian Company in the South Pacific, was published in 1981,followed by The Australian Presence in the Pacific Burns Philp 1914 – 1946 published in 1983and a pictorial volume, South Pacific Focus, Burns Philp’s trading viewed through photographs early this century published in 1986.

I mention this because it was a mark of his sense of fair play that Buckmade me a co-author,to recognise the extent of my research in Vol 1 and extensive contribution to writing in Vol 2 and 3. This approach was not common practice, and principal authors regularly exploited their associates, not giving them due credit. Buck was different.

A part of Buck’s story which especially interests me is his account of the formation of the NSW Council for Civil Liberties. “In the 1950s and 1960s, the New South Wales Police Force was out of control. Besides corruption, especially in the liquor trade, there were numerous press reports of police brutality, often resulting in serious injuries to people held at police stations. There were no serious investigations of such complaints, and the state government fobbed off all criticism” (p153).

There follows the marvelous account of the famous Kings Cross party in February 1963. The incident and the cover up led – as a result of Buck’s persistence – to the founding of the NSW CCL in September 1963. The first step was taken by a disparate mob: Jack Sweeney QC, Dr Dick Klugman and Ken Buckley. “What we had in common was a deep concern for civil liberties, quite without reference to party politics” (p159).

I remember licking endless envelopes to send out notices to prospective members. By mid-1964, there were about 300 paid up members of CCL. The production of a leaflet If You Are Arrested was an early very successful initiative and has it been frequently reprinted and revised. Many different cases came to the CCL: some individual, others concerning broader matters of principle. Besides police misconduct, there was freedom of speech and censorship, immigration and Aboriginal affairs, prisons, gay rights and abortion. There is a dilemma facing civil liberties organisations – should they accept cases from extremist groups who are themselves anti-civil liberties? The NSWCCL was spared having to defend Nazis “…due to the stupidity of the local fascists” (p177).

In its early days “What the CCL provided was an opportunity for relatively poor people to obtain free legal representation, so long as the case involved issues of civil liberty” (p206). The CCL lawyers worked pro bono, often in ground breaking cases. This situation altered with the establishment through the 1970s of such government-funded services as Aboriginal Legal Aid, Women’s Legal Aid, and Migrant Legal Aid bodies.

Their ASIO files reported the marriage of Ken and Berenice Buckley in August 1965, a long and loving partnership which was the mainstay of the NSW CCL for the next 40 years. He became an Australian citizen in 1973.

Of interest in the current circumstance is the introduction in November 1973 of a Human Rights and Racial Discrimination Bill. “The CCL gave strong support to the Human Rights Bill, organising a big public meeting in Sydney and engaging in public controversy on the subject” (p263-4). Debate on the Bill was aborted by the 1974 election and then never reintroduced. The Fraser government subsequently bought in a Human Rights Act, which created a Commission to investigate breaches and make recommendations to government (now the Australian Human Rights Commission).

In 1976, there were philosophical differences in the CCL: a radical group wanted to extend its activities to issues beyond those usually considered as civil liberties. Meeting atmospheres became “cantankerous” in a way that was threatening productive deliberations. Buck took them on, describing the radical group as “nihilist, since it advocates no prisons, no mental hospitals and no representative democracy” (p288). At the AGM, a rallying cry to rank and file members resulted in a return to more moderate leadership.

In 1976 also, there was an attempt to form a national body, an Australian Council for Civil Liberties. Buck was elected first President, but the group failed. “The problem was that most civil liberty problems were State matters, leaving only a few issues, notably censorship, to be dealt with on a federal basis” (p290).

If that was true then, it certainly isn’t in 2009. Issues like the terror laws, sedition laws, data protection, DNA, surveillance, and increasingly executive federal decision making with no input from community groups, as well as a need for a Charter of Rights, euthanasia, freedom of information and protection of whistleblowers, indigenous rights, refugee rights and environmental problems all demand attention of a national body. Buck’s book shows how state-federal power has shifted so dramatically.

Ken and Berenice did not hold official positions for some years after 1983 – which coincided with a decline in the organisation. Buck attributed this to a number of factors, including inconsistent effectiveness and the rise of other organisations acting for disadvantaged people. Single issue advocates devalued the broader concept of civil liberties and membership fell as a result. Buck writes: “The CCL neglected the possibility of its acting as a broad umbrella covering new bodies, at least with reference to civil liberties. We missed the opportunity and paid the price” (p346).

In 1993 Buckley took action to re-establish CCL’s position, with new officers and Buck as a Vice President. He was honoured by life membership in 1994 and several more active years followed, and “1997 was probably the biggest and best year in the CCL since the 1960’s” (p348) due in no small part to collaborative efforts of John Marsden and Buckley. Activities included submissions to commissions, and policies on drugs, gun control, prisons, euthanasia and law reform.

In his final chapter, Buck summarises his view of the role of CCL. “Undoubtedly, the CCL played an indispensable role in bringing about major changes in the climate of opinion concerning civil liberties, and it still serves as a necessary guardian of the rights of underdogs” (p366). His fundamental belief and his persistence, which was the backbone of the CCL, was: “…my conviction that it is necessary to keep on fighting against bureaucrats and authoritarian figures” (p367). Mine too.

We miss him. The nation – and particularly NSW – misses a ‘difficult’ Pom who became a most influential Australian.

Dr Kris Klugman OAM

President, Civil Liberties Australia

May 2009

Buckley’s! : Ken Buckley; Historian, Author and Civil Libertarian – An Autobiography

A & A Book Publishing, 2008. $29.95 plus $7 postage

A&A Book Publishing P/L. PO Box 449, Leichhardt NSW 2040 Australia

Books can be ordered online at www.aampersanda.com