By students of the ANU law social justice program

Freedom of movement is a human right that is fundamental to the realisation of a wide range of capabilities and other rights. During periods of lockdown, the freedom to go for a walk at our own pace, in whichever direction we please, is important to our mental and physical wellbeing.

When business and government began to shut down in Canberra during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, the ACT Supreme Court found that ‘each and every aspect of daily life is now dictated by the emergency. This means that the emergency enables the imposition of laws and regulations previously not contemplated.’

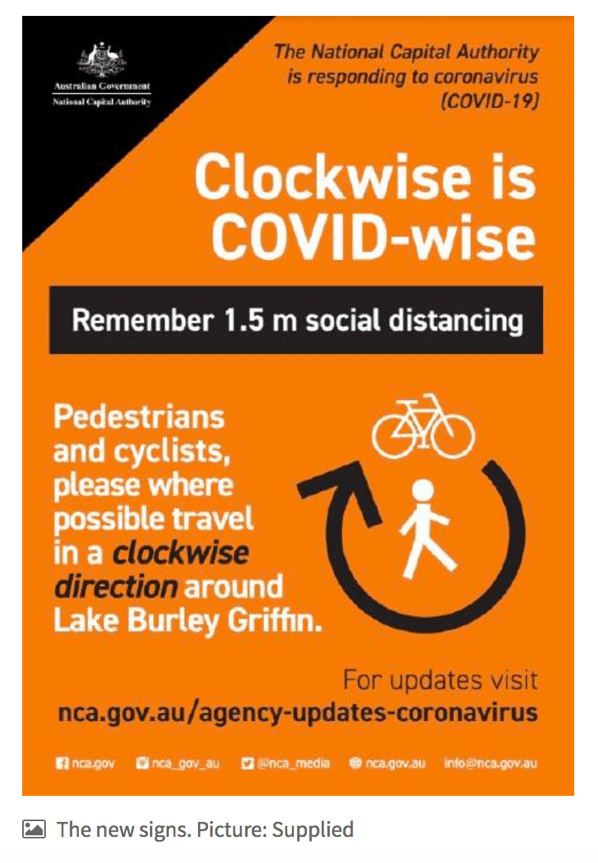

If you walked around Lake Burley Griffin (‘LBG’) during lockdown, you would have seen the ‘Clockwise is COVID-wise’ signs. The advice aimed to prevent the transmission of the virus as it prevented lake-goers passing by one another.

Should this suggestion have been a legally enforceable obligation? Should it have come through an instrument of the Commonwealth or the ACT? The lawfulness of an order to move clockwise around LBG would depend on whether it strikes the right balance between safeguarding our freedom of movement and protecting us from the public health risks of COVID-19.

Should this suggestion have been a legally enforceable obligation? Should it have come through an instrument of the Commonwealth or the ACT? The lawfulness of an order to move clockwise around LBG would depend on whether it strikes the right balance between safeguarding our freedom of movement and protecting us from the public health risks of COVID-19.

The ACT Minister for Health has the power to declare a public health emergency ‘if satisfied that it is justified in the circumstances’. The Minister did so on March 16 2020 and extended the emergency several times thereafter. This empowered the Chief Health Officer (CHO) to ‘take any action, or give any direction, he or she considers to be necessary or desirable to alleviate the emergency specified in the declaration’.

Attached to an infringement of these directions ‘without a reasonable excuse’ was a fine of up to $8,000. Additionally, the CHO ‘may apply to the Magistrates Court for an order that a person to whom a public health direction has been issued comply with the direction’. These are undoubtedly far-reaching powers.

The Public Health (Indoor Gatherings) Emergency Direction 2020, which limited the number of individuals able to attend an indoor gathering, is just one example of such directions. Although a seeming overreaction to someone walking anti-clockwise around LBG, our laws seem to allow this in the name of a public health emergency.

Nonetheless, a CHO direction must be consistent with human rights obligations. Under the Human Rights Act (ACT), it is unlawful for a public authority to act in a way that is inconsistent with human rights, or in a way that fails to give proper consideration to human rights. As a public authority undertaking functions of a public nature, the CHO is bound by the obligations set out in the ACT Human Rights Charter. ACT Policing police officers must also act consistently with the Human Rights Act.

Australia is a party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which provides that ‘everyone lawfully within the territory of a State shall, within that territory, have the right to liberty of movement’. The Human Rights Act (ACT) states the freedom of movement as ‘the right to move freely within the ACT’.

There are several potential constitutional powers which the Commonwealth may have relied on to make the order that individuals walk clockwise around a public space. Among the legislative heads of power are the external affairs power contained in s51(xxix), the quarantine power contained in s51(ix) and the territories power contained in s122. The prerogative power or nationhood power of the executive may also have been a potential source of power that the Commonwealth government could have relied on.

Whether a similar order from a Commonwealth agency would have to be consistent with the Human Rights Act (ACT) is open to interpretation of Commonwealth and state powers. Commonwealth legislation cannot ‘significantly impair, curtail or weaken the capacity of the States to exercise their constitutional powers and functions’ or ‘the actual exercise of those powers or functions’. It is unclear whether fundamental human rights values articulated by the Human Rights Act (ACT) would be considered fundamental to its position as a government separate from the Commonwealth.

Free to run around in circles? Which way?

Australian case law around freedom of movement has thus far dealt exclusively with freedom of movement of individuals moving interstate, rather than limitations on the freedom of movement arising from other contexts such as social distancing measures and lockdown requirements.

Victorian man Julian Gerner has brought a case challenging lockdown restrictions in Victoria under the implied freedoms from the Constitution. Likewise, Clive Palmer has failed in challenging the Western Australian COVID-19 orders around travel restrictions under section 92 of the Constitution, which deems that ‘trade, commerce, and intercourse among the states…shall be absolutely free’.

It is still unsettled whether an infringement on freedom of movement actually covers a directive to move clockwise around the lake, but it is unlikely that such a limitation would rise to the level of an infringement encompassed by the above-mentioned human rights frameworks.

Even if the direction did limit the right, freedom of movement is not absolute and can be subject to certain restrictions. For example, under the Human Rights Act (ACT), freedom of movement may be subject to reasonable limitations.

The Human Rights Act (ACT) sets out the steps for deciding whether a limitation is ‘reasonable’ which requires consideration of (a) ‘the nature of the right affected’ (b) ‘the importance of the purpose of the limitation’ (c) ‘the nature and extent of the limitation’ (d) ‘the relationship between the limitation and it’s its purpose’ and (e) whether there are ‘any less restrictive means’ available to achieve that same purpose.

The High Court of Australia has recently held that the proportionality test for the implied freedom of political communication requires a structured analysis that incorporates the purpose, suitability and adequacy of the impugned legislative provision.

The ICCPR also permits restrictions on this right when the restrictions are ‘provided by law’ and ‘are necessary to protect’, among other things, ‘public health’.

Movement is a fundamental right: but can you choose which way?

In urging that COVID-19 measures be proportionate and necessary, the United Nations Human Rights High Commissioner has described movement as a fundamental right. A less restrictive means for the necessary protection against the spread of COVID-19 which is proportionate to the public health risk may be to require people to maintain a distance of 1.5 metres with others when walking around the lake, or to require people to only walk on one side (for example, the left), rather than requiring people to walk in a certain direction.

Maintaining physical and specifically cardiovascular health was considered to be important for the prognosis of virus victims, and promoting healthy lifestyles despite the requirement to stay at home seemed to be one of the aims of the Australian government in establishing the rules. COVID-19 measures may not only infringe on fundamental rights, but may also worsen mental health issues, including mental distress fuelled by the requirements of distancing and isolation

Obliging Canberrans to walk around LBG in a particular direction creates unnecessary additional planning, potential inconvenience and mental distress leading some to abandon the walk entirely. Additionally, the risk of transmission from passing others on a walk has been assessed as extremely low.

Had the request to walk clockwise been made mandatory under the Public Health Act 1997 (ACT), what options would the public have to challenge the requirement?

Under the Public Health Act 1997 (ACT) itself, an individual has a right of appeal to the Supreme Court in relation to an order made by the Magistrates Court. This may provide a means of challenging the penalties associated with infringing a public health direction.

The Human Rights Act also gives the ACT Supreme Court authority to decide when a public authority, such as the CHO, contravenes a human right listed in the Act and provides any remedies it deems necessary. However, the Supreme Court cannot award damages under the Human Rights Act.

Should pollies decide which way they are for turning?

Another option may be to challenge the decision of the CHO under the ACT Supreme Court’s constitutionally entrenched supervisory review jurisdiction. Nonetheless, the variety of people affected by COVID-19 and the competing interests that must be considered in making such decisions may lead a court to determine that such issues are not justiciable in that they are better determined in ‘the political arena’.

An individual may also make an application for the law to be judicially reviewed under the Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1989 (ACT) if they can show themselves to have a person aggrieved by the administrative decision. Nonetheless, the costs associated with judicial review of administrative decisions are exorbitantly high and as such create a barrier to access the review.

The current scheme reveals significant gaps in individual’s access to remedies for the infringement of human rights under the Human Rights Act (ACT). The ACT Supreme Court’s lack of authority to award damages renders retrospective litigation of human rights infringements futile. This is particularly aggravated in the context of rapidly changing legislative responses and government policies required to match the rate at which the Pandemic advances.

Additionally, costs associated with litigation create an impasse between a human rights framework and the protection of those rights.

A possible solution to this impasse is reflected in the alternative dispute resolution mechanisms available under the Human Rights Commission Act 2005 (ACT) with respect to unlawful discrimination. The Human Rights Commission for example, has the capacity to conduct an investigation of any complaint it receives by a person under the Discrimination Act 1991 (ACT). It may also attempt to resolve the dispute via conciliation. It also has the power to refer the matter to ACAT for resolution on the request of the applicant.

A similar method for contravention of the Human Rights Act may allow for more efficient access to justice during the COVID-19 pandemic.

If it is argued that the ambit of the Human Rights Act (ACT) is limited to the protection of human rights, a Commonwealth legislation dealing with COVID-19 orders is very likely to cover the same subject area of affecting or restricting rights. The Human Rights Act (ACT) implies an intention to regulate the ‘whole field’ and protect fundamental human rights in the ACT, whereas Commonwealth legislation making restrictive COVID-19 orders regulates the same field to restrict rights to address a public health risk.

Did other pandemic instructions infringe on liberties and rights

Commonwealth legislation would articulate the intention to ‘express by its enactment, completely, exhaustively, or exclusively, what shall be the law governing the particular conduct’ of ACT citizens in limiting their freedom of movement. As such, the Human Rights Act (ACT) may be rendered inoperative while a valid Commonwealth legislation restricting fundamental rights will remain operative.

It seems trivial to embark on such a serious inquiry about the legality of a direction to walk clockwise around a lake. However, the speed at which the pandemic is evolving and scientific knowledge is developing has posed significant administrative law questions.

We must ask the question of whether a public health order has a valid reason to infringe on civil liberties. The Australian context poses particular challenges in relation to the frameworks around Commonwealth and state orders, and which – if any – human rights safeguards apply.

When public authorities are vested with sweeping powers to affect very intimate aspects of our personal lives, it becomes more pressing to hold decision makers accountable to human rights obligations.

ENDS

Organised by Civil Liberties Australia in conjunction with the Law Reform and Social Justice students at ANU. Student author contributors: Sherine Al Shallah, Shenpaha and Ganesan Rose Kethel, with editing by Jessica Hodgson, Jess Honan and Jeffrey Weng

CLA Civil Liberties Australia A04043

Box 3080 Weston Creek ACT 2611 Australia

Email: secretary@cla.asn.au

Web: www.cla.asn.au

2021_03_13

Congratulations on this meticulously researched and comprehensive analysis. The tests of necessity and proportionate official response in imposing such extreme restrictions have never been met. Analysis of relative risk was and is conspicuously absent (infection with CV19 from passing another person walking around Lake Burley Griffin, in the open air? Negligible to non existent. How absurd). Judicial officers, politicians, and the biomedical bureaucrats they outsourced decisions to assumed without reliable information that the CV19 risk was catastrophic, without objective scrutiny of the evidence. Far reaching “instant noodle” draconian infringements upon personal autonomy and freedom were and are based on defective computer models measuring, or claiming to measure, only one dimension of risk, ignoring legal, social, economic and other vital issues. Cringing hermitry is not life, and the burden of proof rests solely with the advocates of such illiberal control.

Many thanks for this in-depth analysis of the legality, medical necessity and socio-psychological impact of the “clockwise is covid-wise” example of Commonwealth legislation restricting the Human Rights Act. I particularly take away from your analysis, that given the current legal conventions of legislators, legal and illegal options for an individual disagreeing with the legislators are costly and evidence what the law currently is powerless to do, undermining legal loyalty. It leaves the individual therefore to focus on creative political action to develop legal tools of civil response.