Ken Davidson, editor of Dissent magazine and also a leading columnist on The Age newspaper, has analysed in straight economic terms why the current approach to drugs is wrong. He supports a switch to low-cost, high-impact programs.

Ken Davidson, editor of Dissent magazine and also a leading columnist on The Age newspaper, has analysed in straight economic terms why the current approach to drugs is wrong. He supports a switch to low-cost, high-impact programs.

Time to start thinking again on drug laws

By Kenneth Davidson*

Huge profits ensure that new traffickers are = always ready to fill any gaps

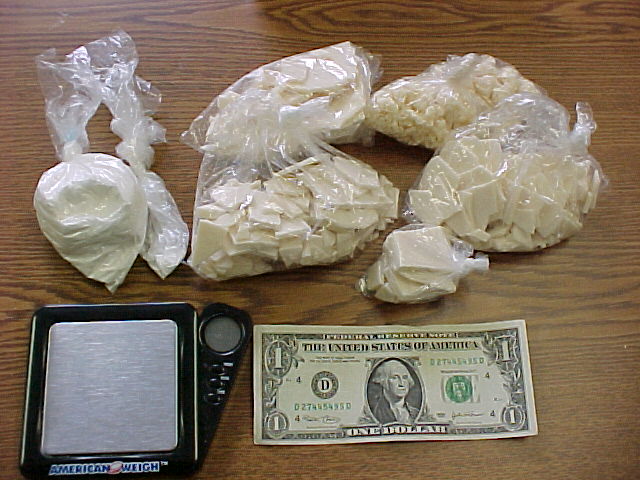

The report by The Age and Four Corners on a major drugs bust (code-named Operation Hoffman) by state police forces under the direction of the Australian Crime Commission was a cracking story. A fascinating cast of goodies and baddies was set against the background of a global drugs distribution chain, which was broken by following the money trail.

The conclusion was that even with regular disruptions to the supply chain and the operators being given heavy jail sentences, the extremely high profits are more than enough to ensure that new drug rings will step into the breach.

If interruptions to supply chains were working, we would see low availability of drugs and high prices leading to reduced consumption. Evidence from overseas – where the policy emphasis is on cutting supplies – shows that drugs are in fact more readily available, prices have fallen dramatically, the purity of hard drugs is increasing and the market is growing.

But the conclusion drawn by the crime commission from Operation Hoffman is that it needs more resources to follow the international money trail.

The 2008-09 Illicit Drug Data Report ramps up the rhetoric. The drugs of choice for today’s young are amphetamines and ecstasy. The report states that amphetamines, even in small doses, can cause cardiovascular problems and convulsions leading to death. Long-term use can trigger violent behaviour, and structural and functional changes to the brain, leading to psychosis.

According to the commission, ecstasy (in high doses) can result in liver, kidney or cardiovascular system failure and death. Long-term use can cause paranoia, insomnia, nausea, hypothermia and severe hallucinations, and can damage cognitive and memory functions.

I am sure that this is true, but it should be kept in proportion. The damage done to individuals and the harm caused to society by these drugs (even the most lethal illicit drugs, such as heroin) is small compared with the harm done by legal drugs such as alcohol and tobacco.

According to a 2003 study undertaken for the British cabinet, and later published by The Guardian, heroin and/or crack users were responsible for the vast majority of the cost of drug-motivated crime, ecstasy was unlikely to cause significant health damage, and amphetamines had medium health risks.

Heavy use of amphetamines or ecstasy could affect users’ ability to work and to care for others, but was unlikely to motivate crime.

Attempts at supply intervention should be concentrated on ”hard” drugs, because heroin and/or crack users are the ”high harm-causing users”.

But as the British report said, even if supply interventions did successfully increase the price, the evidence was not sufficiently strong to prove that this would reduce harm. While shortages might drive some users to get treatment for their addiction, it might also induce some users to undertake more criminal activity to satisfy their addiction.

Let’s put this into a historical context. Up until 1906, it was legal to import edible opium into Australia.

In a speech to the Lowy Institute, Alex Wodak, the director of alcohol and drug services at Sydney’s St Vincent’s hospital, quoted the 1908 annual report to the Commonwealth Parliament by the comptroller-general of customs, which said: ”It is very doubtful if such prohibition has lessened to an extent the amount which is brought into Australia …

”Owing to total prohibition, the price of opium has risen enormously … the Commonwealth gladly gave up about £60,000 revenue with a view to a suppression of the evil, but the result has not been what has been hoped for. What now appears to be the effect of total prohibition is that, while we have lost the duty, the opium is still imported freely.”

Victimless crimes – ranging from drugs to prostitution – are a sure-fire recipe for police and political corruption. Alcohol prohibition in the US led to corruption and organised crime.

Prohibition encourages consumers and suppliers to focus on drugs offering the greatest ”hit” (and health risks) for users and the greatest profits for suppliers.

Greater expenditure on law enforcement, as advocated by the crime commission, goes against the trend in most countries (including Australia), which sees illicit drugs as primarily a health and social issue.

As drug reform pioneer Wodak (who introduced the first safe, but illegal, injecting facility in Australia) argues, the war on drugs has failed comprehensively and the political elites know that prohibition does not work. It continues because it is politically popular.

According to Wodak, penalties for drug possession and consumption should be eliminated or reduced. He points out that resources allocated to high-cost but low-impact sectors such as customs, police, courts and prisons should be switched to low-cost and high-impact health and social programs.

Reforms would include regulation and taxing the sale of cannabis and possibly allowing the sale of some drugs in diluted small quantities, as was the case with edible opium before 1906, or cocaine in Coca-Cola before 1913.

Kenneth Davidson is co-editor of Dissent magazine, and a senior columnist with The Age newspaper. He is a member of CLA.

This story was found at: http://www.theage.com.au/opinion/society-and-culture/time-to-start-thinking-again-on-drug-laws-20100905-14vxi.html